Posted on

Nov 12, 2025

Stroke Saved, Survival Unchanged: The LAA Closure Paradox

STROKE SAVED, SURVIVAL UNCHANGED: THE LAA CLOSURE PARADOX

In cardiac surgery, some decisions are straightforward. Others live in the grey zone; where evidence is mixed, traditions vary, and the “right” choice depends on who’s holding the scalpel. One such debate: Should we close the left atrial appendage (LAA) during mitral valve repair in patients who don’t have atrial fibrillation (AF)?

A recent national registry study has brought fresh data to the table, suggesting the answer may be more nuanced than we thought.

WHY THIS MATTERS:

The LAA is notorious for harboring thrombi in patients with AF, and closing it is almost reflexive in that population. But in patients with normal sinus rhythm, its role in future stroke risk is less certain.

The potential upside: A one-time closure could prevent strokes down the road.

The potential downside: Added procedural steps, possible complications, and the risk of triggering new arrhythmias.

Surgeons have been operating in this space with more instinct than evidence, until now.

Using a national database of 38,597 patients who underwent isolated mitral repair between 2010 and 2019, investigators narrowed the field to 10,810 patients without AF and without complicating conditions like prior cardiac surgery or endocarditis.

Of these patients:

1,875 (17%) had LAA closure during surgery.

8,935 (83%) did not.

A rigorous propensity score match balanced 27 baseline variables, yielding 1,875 patient pairs for direct comparison.

RESULTS:

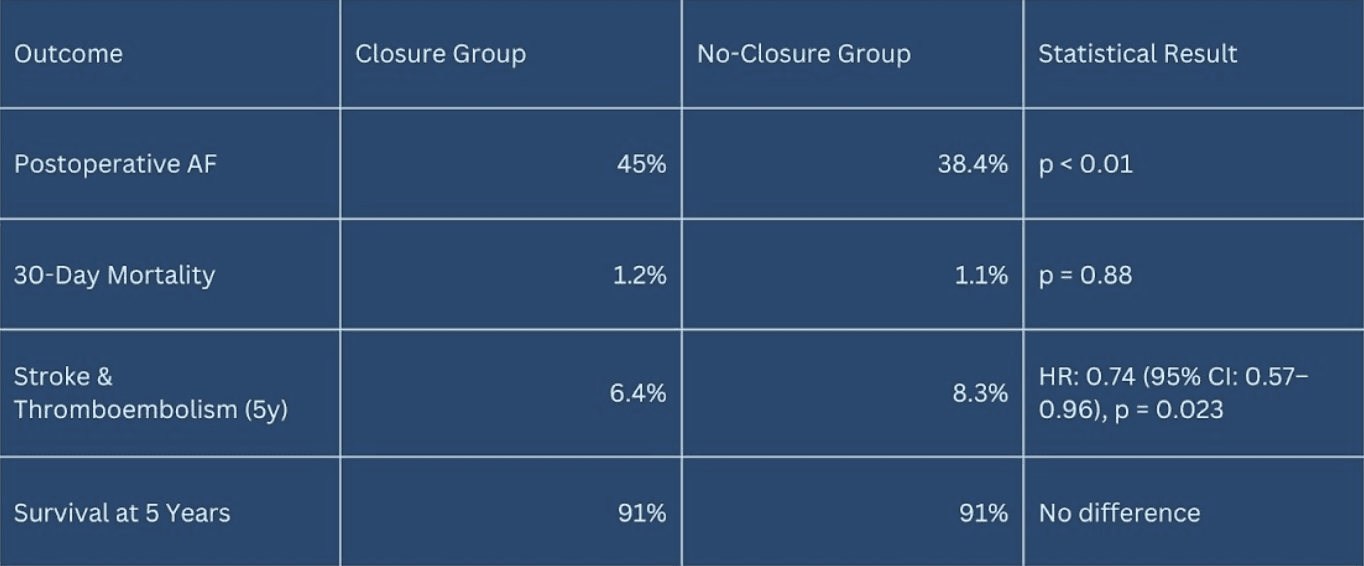

WHAT THE TABLE REALLY SHOWS:

The numbers tell a mixed story. LAA closure did not change survival, but it did reduce stroke and thromboembolism rates over five years; a meaningful outcome for many patients. This study doesn’t give us a universal “yes” or “no.” Instead, it strengthens the argument for patient-specific surgical decision-making:

Older patients with elevated CHA₂DS₂-VASc scores may tilt toward closure for stroke prevention.

Lower-risk patients may see the AF trade-off as too high.

For now, the decision sits at the intersection of data, experience, and patient preference.

LOOKING AHEAD:

The next leap forward will come from prospective randomized trials, moving beyond the limitations of registry data to provide controlled and definitive comparisons. Such trials would not only clarify the true balance of risks and benefits but also help identify subgroups of patients most likely to derive protection from stroke without excess harm.

In parallel, advances in real-time imaging integration, computational modeling, and patient-specific risk stratification could refine surgical decision-making. Together, these tools may allow clinicians to tailor left atrial appendage closure more precisely—predicting which individuals stand to benefit most from the procedure while minimizing the ‘arrhythmia price’ that currently accompanies it.

CONCLUSION:

Prophylactic LAA closure during mitral repair in patients without atrial fibrillation is not a one-size-fits-all intervention. While it offers a modest but clinically meaningful reduction in late stroke and thromboembolism, this benefit is offset by a higher incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation and no demonstrable survival advantage.

These trade-offs highlight the complexity of balancing immediate surgical risks with long-term outcomes. Until stronger, prospective evidence emerges, the most prudent course may be a tailored approach: guided by validated risk scores, the technical expertise of the surgical team, and, importantly, the patient’s own values and preferences. Such individualized decision-making respects the nuances of patient care and avoids the pitfalls of adopting a blanket policy for all.